Welcome, Aanii to State of the Bay! Download the 2023 magazine or technical report.

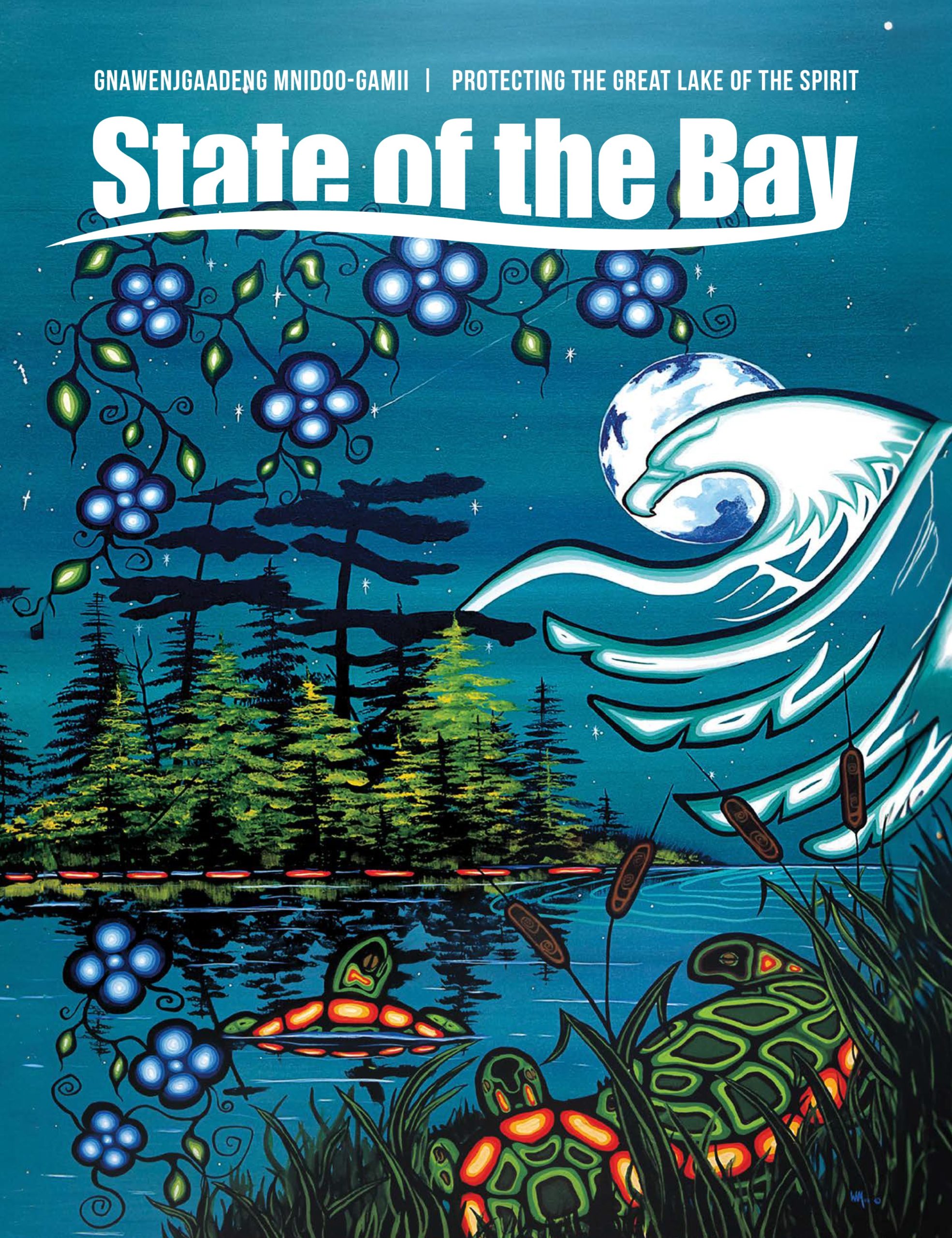

Cover Art: “Tranquility”

“Tranquility” by William Anthony Monague (1956-2019) “Abwaudung” (The Visionary or Dreamer). Self-taught Beausoleil First Nation artist William Monague grew up with the People of Chimnissing. In his piece, “Tranquility” painted in 2001, the painted turtles (mskwaadesi) embody the symbol of healing and the reconstruction of Mother Earth. The Eagle represents the Ojibwe belief of the messenger answering our prayers; giving us the gift of strength and protection. Miigwech to Brenda St. Denis and for reprint permission from the Estate of William Monague.

Intertwining Science, Spirit, & Story

Since 2008, the State of the Bay program has been working to bring together multiple sources of information to communicate environmental changes in eastern Georgian Bay, known in the original language of the territory as Mnidoo-gamii, Great Lake of the Spirit.

Working with partners, the Georgian Bay Mnidoo Gamii Biosphere (GBB) gathers available research about water, wetlands, fisheries, and habitats in this unique landscape and shares this information with people who care about Georgian Bay.

For this third edition of the State of the Bay magazine, it was clear that a deeper understanding of the changes happening to the lands and waters would be created by bringing together stories from elders, knowledge holders, researchers, and scientists.

So, with the help of many cultural advisors, we are taking a new approach—one that values both Indigenous knowledge and western science. Indigenous ways of knowing and storytelling are infused with ethics and teachings, worldviews and values about how to live in a good way—in a way that sustains our community and our non-human kin.

For too long, these knowledge systems have been divided, and Indigenous knowledge suppressed through colonization and racism, while western science has been privileged and the earth has suffered.

Elder Albert Marshall

Integrating worldviews has been called weaving, or braiding, knowledge. It has been taught as “Two-Eyed Seeing” by Elder Albert Marshall of Eskasoni First Nation, a concept he calls Etuaptmumk in the Mi’kmaw language.

In Anishinaabemowin (or Nishnaabemwin), the language of Mnidoo-gamii, a similar concept has been shared as “Seeing Both Sides,” or Edwi-waabndamang, by language speaker Waabishki-makwa, Dr. Brian McInnes of Wasauksing First Nation.

The stories shared in these pages are about appreciating the life and spirit of this place, acknowledging the gift of land, water, sky, and all beings, and doing the work of protecting the Great Lake of the Spirit, Gnawenjgaadeng Mnidoo-gamii.

It is our shared love of this place that brings us together in trying to care for and protect Mnidoo-gamii. We are learning how science and Indigenous knowledge inform one another, creating a richer story of what is changing and how we share a profound responsibility to restore and care for this place, now and for future generations.

The Georgian Bay Mnidoo Gamii Biosphere is extremely grateful to the individuals who have gifted this publication with their time, language, art, and ways of knowing. We are grateful to the many organizations and individuals that contribute scientific research and monitoring to this work. It is impossible to list the names of every individual who has influenced this work over the years. If we have forgotten your name, please know that we are very grateful for your guidance.

- Aisha Chiandet

- Alanna Smolarz

- Angel Wikamakis

- Angela Vander Eyken

- Anita Chechock

- Arunas Liskauskas

- Autumn Smith (Mishiikenh Kwe)

- Benjamin John

- Billie-Jo Isaac

- Brady Carpenter

- Brian McInnes (Waabishki-makwa)

- Chad Fraser

- Christine King (Waabkanii Kwe)

- Colette Isaac

- David Bywater

- David Johnson

- David Sweetnam

- Dawson Bloor (Bidwayodaam)

- Debbie Jackson

- Deina Bomberry (Ozawaanimkeeqwe)

- Emma Petahtegoose

- Erika Kolli

- Gracie Crafts (Niizhogiiziskwe)

- John Rice (Zahgausgai)

- Johna Hupfield (Naawtinokwe)

- Katrina Krievins (Project Manager)

- Kyla Judge (Zhowshkawabunokwe)

- Kyra Simone

- Laura Thipphawong

- Marilyn Capreol

- Melizza Claydentabobondung

- Michele Ten Eyck

- Mike Waddington

- Millie Williams

- Nadine Perron

- Oscar Crafts (Oshkibewis)

- Sandra Lockhart

- Sarah Koetsier

- Sherrill Judge (Midwewekamigokwe)

- Shilah LeFeuvre

- Taylor Judge (Nanowaygahkekwe)

- Tianna Burke

Becky Pollock, PhD.

Executive Director

UNESCO Georgian Bay Mnidoo Gamii Biosphere

Greg Mason, MSc.

Director of Operations

UNESCO Georgian Bay Mnidoo Gamii Biosphere

All Our Relations

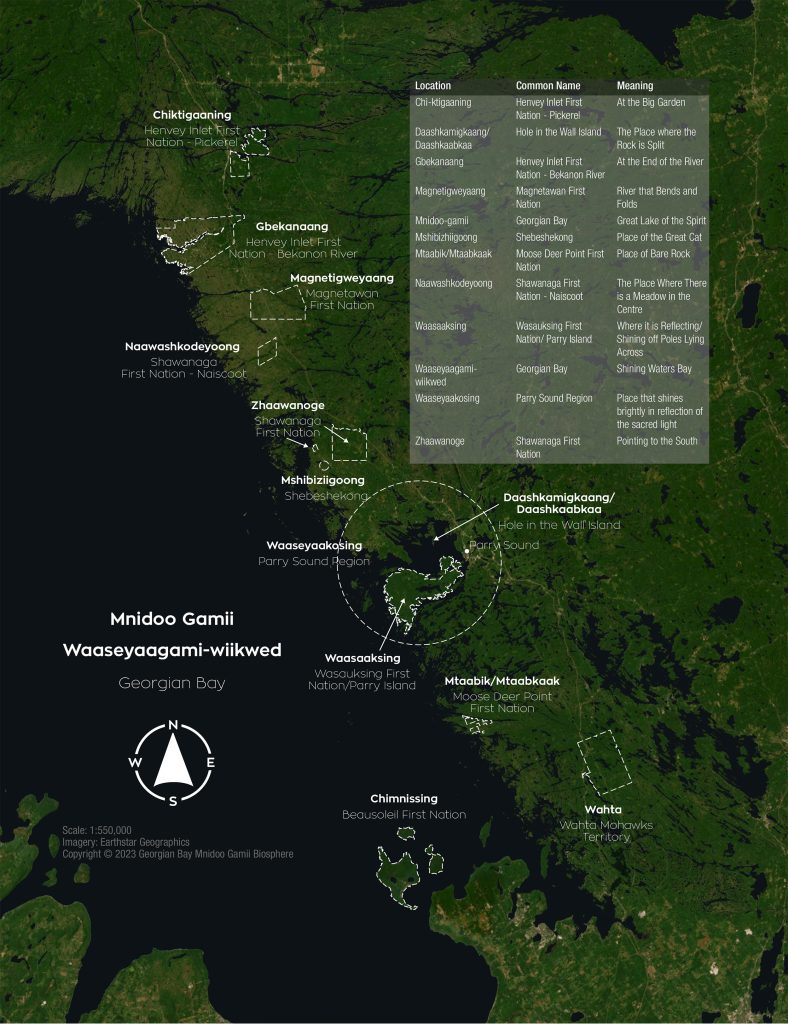

The Georgian Bay Mnidoo Gamii Biosphere gratefully acknowledges that we are located on Anishinaabek territory and that our office is currently located where the Ziigwan (spring) or Gizhiijwan (fast-flowing river) meets Mnidoo-gamii, Great Lake of the Spirit.

We respect and recognize the inherent rights and governance of the Anishinaabek pre-confederation and acknowledge the rights recognized in the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 and the Williams Treaty of 1923.

There are a diversity of Indigenous cultures across Turtle Island. We honour the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and we strive to meet the Calls to Action set out by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

We are committed to our responsibility of relationship building with Indigenous peoples and respect their knowledge and ways of being.

We appreciate each of the communities in the region and thank them for sharing their knowledge and time with us.

- Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory

- Dokis First Nation

- Henvey Inlet First Nation

- Magnetawan First Nation

- Shawanaga First Nation

- Wasauksing First Nation

- Moose Deer Point First Nation

- Chimnissing First Nation

- Wahta Mohawks

- Moon River Métis Council

- Georgian Bay Métis Council

Our organization is privileged and is working to unlearn some of what we have been taught and decolonize our ways of knowing and being. We need to hear the truth so we can reconcile with our past, create new relationships, and move forward together in a good way.

We wish to honour Indigenous resilience since time immemorial. We wish to express our gratitude to our Indigenous relations for continuously leading the way in sustainability, respect, and reciprocity.

We are grateful, Mother Earth. Miigwetchwendam Shkakmigkwe.

Caretakers of This Land

If we are to consider ourselves as the true caretakers of this land, it is necessary that we live and understand our own culture, history, language, and traditional values. The teaching of our Elders must be sought after and honoured. Those with the intimate knowledge and ways of our people and land must be honoured and woven into the very fabric of our lives. The hope, the vitality, and the contemporary views of our youth are sought after and needed so that we can move forward in this joint effort.

Elder Stewart (Zhngos) King, Migizi gii-odoodeman, Wasauksing First Nation

Turtle Island, as it is known by the original inhabitants of this land, is considered sacred and remains a sanctuary and a place of affinity for all natural people. Our Creation story tells of our connection to this land, to the plant life, and to all living things. Our original instructions tell us that we must take care of all things placed here for us, and that they would provide for us during our lifetime. Our people were given a very specific language to communicate with all living things, both physically and spiritually.

Elder Stewart (Zhngos) King, Migizi gii-odoodeman, Wasauksing First Nation. Excerpt from the 2011 Parks Canada publication “Working Together: Our Stories.”

Nishnaabemwin: The Language of the Bay

Nishnaabemwin, the language of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples, is an original language of Mnidoo-gamii. The Nishnaabeg (“the good beings”) recognize their language as a sacred gift from the Spirit and know it to be representative of their original values, practices, and unique ways of thought. Nishnaabemwin is a highly adaptive language that matches the resilience and adaptive capacity of Indigenous nations. It is spoken throughout the Great Lakes region and beyond, in both Canada and the United States.

Despite the broad distribution and historic strength of the language, hundreds of years of colonial practice have decimated speaker numbers. We honour the efforts of Indigenous communities to revitalize and restore their language. Each of the local communities in Mnidoo-gamii are still blessed with fluent master language speakers whose words and wisdom are perhaps more important now than ever before.

We recognize and honour the various dialects of the Nishnaabe language (such as Anishinaabemowin, which is spoken further north and westward) and other Indigenous languages (such as Mohawk and Cree) that can be heard in the local region today. The increased diversity of languages and cultures has added special value to life in Mnidoo-gamii. Nishnaabemwin, which is resonant with the natural sounds of this place, holds unique value and positionality as the first language of the bay. It is why the sacred ceremonies and prayers of the Nishnaabe people continue to be made in their original language. It is the language that the land, water, and spirit of this place best understand.

Indigenous languages did not originally use an alphabetic writing system with symbol-sound correspondences. Evidence of historic Indigenous writing systems can still be found throughout Mnidoo-gamii in rock paintings and on birch bark scrolls. Traditional artistic expression, such as beadwork or quillwork, was occasionally representative of these historical writing systems, which more encoded stories or teachings as opposed to words. The double vowel system is the most popular way that Nishnaabemwin is written today. Having a semi-standardized writing system has been extremely helpful to the expansion of the language into educational, written, and technological domains. Various phonetic or syllabic orthographies have also been developed and may find expression in these pages. Any writing system works equally well, provided it is consistently and accurately used. What is most important, especially for an oral language such as Nishnaabemwin, is that the written guide supports the expressive use of the language.

Some basic principles of the double vowel system as it relates to the contemporary expression of Nishnaabemwin are shown here. This is a roman orthography, which uses many characters and sounds (such as consonants) that are already found in the English language. A few unique pronunciation features of the double vowel system are highlighted below.

Vowels

Nishnaabemwin is written with seven vowels—three short vowels and four long vowels. The following chart lists some English language words that have similar sounds.

Short Vowels

a

“but”

i

“pit”

o

“okay”

Long Vowels

aa

“saw”

ii

“key” or “see”

oo

“coat”

ee

“leg” or “flag”

E.g. Mnidoo-gamii – Say: Min-i-doh gumee

Glottal Stop

A glottal stop is caused by a momentary pause or stoppage of breath. This is written in Nishnaabemwin with an apostrophe, as in de’ (“heart”) or wen’enh (“namesake”). This is a similar sound as found in the English expression “uh-oh.”

−Waabishki-makwa, Dr. Brian D. McInnes, Wasauksing First Nation, University of Wisconsin

Mnisinoog: Warriors for the Bay

Wasagaam ezhaayaan

To the other side of these waters do I travel.

Bmaashkaa bmaashkaa

The waves go along, the waves go along,

Ondaasgaam ge-giiweyaan

To this side of the lake will I return.

−Ojibwe Song

Many years ago, I was visiting with my great uncle Duncan Pegahmagabow on the Wasauksing reservation on Georgian Bay. The sun was setting over the water when the wind shifted direction and the dark blue waves were suddenly arrayed in yellow, orange, and brilliant red light. Then, as quickly as it had begun, the wind settled, and the colours of the fading day soaked into the dark, still water. A gentle peace descended upon us as my uncle acknowledged the completion of the sun’s work that day.

“Miigwech nmishoomis—thank you grandfather,” he said. His gentle Ojibwe words passed along the water before being carried off by the wind. It was a beautiful convergence of many things that my uncle summed up with one final word that evening: “Mnidoo.” The spirit. I have often thought of that moment while travelling through the waters of Mnidoo-gamii— the Great Spirit Lake. It is a name that encapsulates the beauty, strength, and sacredness of the bay. It is also a name that no human being bestowed upon this place. It was instead Nenabozho, the great cultural hero of the Nishnaabe people, who first walked these shores and declared the forever name of this place. There were six such sister gamiin—the Great Lakes—but Mnidoo-gamii (Georgian Bay) was the Great Lake of the Spirit. It was a shared territory, of spiritual beings and humankind.

Merfolk swam in the deepest parts of the bay, seen only for an instant on the warm rocks of summer before disappearing into the depths. Giant white turtles and sturgeon—the chiefs of all the water beings—surveyed the extremities of their domains, while tribes of little people looked after the shorelines and sacred rock domains. Offerings of sacred tobacco were left for them all, and always for the great water lynx (mshibizhii), whose blessing was needed for safe travel and a successful catch. The First Peoples learned to live with respect for the totality of the natural world—including both physical and spiritual domains.

In the old legends of the Nishnaabe people (“the good beings”), Mnidoo-gamii was created by the spirit guardians as a place of great richness and power. The ancient rock base of the Canadian Shield— amongst the oldest in the world—was said to contain all the wisdom and memory of the world. Shaped by the four elements, including the legendary journey of the great ice to the forever winter lands of the north, Mnidoo-gamii would become a sanctuary for both living and spiritual beings.

When conditions were ready for the First Peoples to be born, Nenabozho rose from his place on Manitoulin Island (Mnidoo-mnising) to make his storied walk throughout the landscape. The names and stories he gave to the world preceded human life but not human purpose—they would be, in many circumstances, the very reasons that humans came to be. The earth was filled with meaning and destiny before the first humans left their tracks in the sand—and they were gifted with a special charge for maintaining the sanctity of this place and the memory of its story. Georgian Bay has one of the most diverse geographies of any Great Lake, perhaps other than Lake Superior (Gchi-gami). From its towering bluffs, long, flat beaches, and seemingly endless channels that stretch far into the interior, it remains a place of both majesty and mystery. Each of the gamiin were distinct to the First Peoples. With their own names, stories, songs, and purpose, these lakes were connected to each other through a series of channels and even underwater passages.

Water—nbi—was the lifeblood of Mother Earth and essential for all existence. But so too was a comprehensive knowledge of the world. A sense of respect, and an innate curiosity for the scientific underpinnings of the world, characterized Nishnaabe experience in the world. The ability to receive spirit messages of healing and direction, combined with keen skills of investigation, observation, and analysis, helped ensure life would always be more than survival.

Nishnaabe people today still recall when there was no sickness that couldn’t be cured through traditional medicine. The earth was a place of both revelation and introspection. Learning how to use available resources most productively and sustainably was all a part of mnobmaadziwin—the good life, for the Nishnaabeg.

All of the stories about how the First Peoples come to Mnidoo-gamii are connected to the guidance of the Great Spirit—Gchi-mnidoo—during a time of need or change. In one compelling story still told today by Nishnaabeg along the eastern shore, a young boy went fasting during a great hardship. After breaking his fast early, he wandered the land while plagued by endless hunger and continuous growth until he dwarfed even the tallest trees.

After a long journey throughout the Great Lakes region, he came upon a young woman who was afflicted by worry about the fate of her people, who were searching the landscape for a new homeland. The boy agreed to help her by scooping up some sand with his giant hands and blowing it off to a distant and uninhabited place. As the grains of sand fell into the waters, they became a vast chain of islands that would provide sanctuary and protection for the young girl’s people. This story of redemption ends with the boy being rewarded with an end from his ceaseless wandering and the young girl finding a new home that would never be taken away from her people. It is also within this story that the famous 30,000 islands find a place within the spiritual history of the Nishnaabeg.

The story of the great migration, expertly recounted by Ojibwe oral historian and ceremonialist Edward Benton in The Mishomis Book, details how the mainstay of the Ojibwe Nation travelled from their home on the eastern shore of Turtle Island to find a home in the interior of the continent. Guided by the words of eight spirit prophets who emerged from the Atlantic, the people set out to find a new home that would be revealed by freshwater oceans and food that grew on top of the water. They were told to watch for signs along the way—namely the appearance of a great spirit shell in the sky at seven different places.

This journey, which would take generations to complete, passed through Mnidoo-gamii, where the nation may have paused the longest. There was a familiarity about the land and water here—and the people developed a love for this place. The presence of mnoomin (wild rice)—the prophesied food that grew on the water—left many to wonder if this was the new homeland they’d been seeking. In time, however, the sacred shell emerged from the place of bright water (waase-biishing) and shone its light upon the eastern shore of the bay. The journey for the Nishnaabeg would continue—but not for all.

The bright light that shone upon the eastern shore of the bay proved an epic moment that left its mark upon the land and the hearts of the people. It was unquestionably time for the nation to continue westward and leave this place that had been home for generations. It was not entirely about the great shell that appeared in the sky and cast its light upon the land: how the land responded proved of equal consideration. The white colouration of the sand, metallic and crystalline rock, birch trees that lined the shoreline, and the bleached teepee poles along the beaches, reflected the shell’s light in almost perfect luminescence: Waaseyaakosing—the place that shone in reflection of the sacred light. The end of summer marked the point at which it became necessary to travel onwards for the mainstay of the nation. The encampments from Wasaagiing (Wasaga Beach) to Mnidoo-mnising (Manitoulin Island) were retired and abandoned, save for some select groups that elected to remain behind. In honour of the great reflection of the spirit light in this place, many vowed to remain and protect this new eastern doorway of the nation.

The Nishnaabeg, who shared much of the bay with the Huron Nation, maintained a peaceful and progressive co-existence. An exchange of goods and customs was a part of their relationship, but so too was a mutual respect and friendship.

Mnidoo-gamii connected multiple regions and groups in a vast pre-Columbian intercontinental trading network. The Nishnaabeg benefitted from participating in this exchange, which enhanced local culture and life. All such visitors were awed by the abundance of the bay and the good life it provided. The majestic old-growth forests reached to the heights of the sky and merged blue and green into a single colour in Nishnaabemwin—the language of the people. The waters provided an endless source of fish, and the land rewarded the people’s hunting and agricultural pursuits. In time, the Ojibwe who stayed behind would join with their Odawa and Potawatomi relatives in a new age of strength and prosperity under the Three Fires Confederacy of nations. Through times of war and peace, the Nishnaabeg found strength in the spirit of the land and each other.

The four winds (niiwin wendaanmak) were prominently honoured and beseeched Mnidoog (Spirit Beings) whose blessings could ensure calm travel but also bend the largest pines and rock to their will. Evidence of their influence could be seen everywhere in the bay—in both the lasting changes they made to the land but also in how quickly still water could become a mighty tempest. There is not a rock, tree, or parcel of shoreline that has not been influenced by the winds and water. So powerful were the whitecaps (waabi-dgowag) that the Nishnaabe would describe them as animate beings—composed of inanimate water but with a spirit life all of their own.

This deep connection to the natural world became reflected in the thought and language of the people. Wasauksing Elder Fred Wheatley would often say that you could hear the unique sound of the land in the way the people of a region spoke. It is for this reason today that language remains one of the most important cultural aspects of Mnidoo-gamii—encapsulating words, ideas, and stories that frame a respectful and good way of living with the earth.

The story of how the 30,000 islands (mnisan) were formed in Mnidoo-gamii describes more than the creation of a physical home. It provided the people with an unbreakable strength and spiritual grounding in the land. It is, therefore, no surprise that the Nishnaabemwin term for warrior—mnisinoo—would also originate from this same connection with nature. The islands exist together as a seemingly endless and unbreakable collective. No two are alike, but they stand together as one—enduring some of the most extreme forces of nature with steadfast resilience. It is a construct that is also metaphorical of the distribution of Indigenous lands throughout Mnidoo-gamii today.

The reserve lands—aptly called shkon’ganan (that which is left over or saved) represent a mere fraction of the totality of lands lost by the Nishnaabeg. Part of our collective work today is to recognize the enduring connection that Indigenous peoples have to their complete original homelands and to respect and advocate for their enduring rights of access, stewardship, and even compensation.

A related task is to recognize what it means to live in a shared homeland in Mnidoo-gamii—the Great Lake of the Spirit. Protecting these sacred waters is a responsibility we all share today. We can find inspiration from the warrior tradition of the Nishnaabeg, whereby each individual stands as an island in defence of the land with all others. Continuing to learn from the Nishnaabeg, using the original place names, and helping restore the first language and stories of this place are all part of defending Mnidoo-gamii today. We must all stand together through the storms of the present, as allies and relatives, in defence of this new shared homeland that we must seek to protect for the next seven generations ahead.

−Waabishki-makwa, Dr. Brian D. McInnes, Wasauksing First Nation, University of Wisconsin

Artist’s Statement by Mishiikehn Kwe

This piece is called Seasons because it depicts the four seasons. In each season, there are plants and animals that sustain us through those seasons. The turtle represents creation, the land we live on, and the moon cycle.

The sun rises in the east, on the yellow line that represents that direction, as well as the spring season. The plants are fiddleheads and black spruce buds, which are harvested in the spring. Below is the summer season, under the southern direction and in the direction of the red line. There are blueberries, strawberries, and roses. The sun is shining, and the days are longer.

The fall is when we harvest moose and cranberries. The fall is in the western direction, on the black line. The days start to get shorter here, so there are more stars than blue sky, as in the spring and summer months.

Finally, the winter is when my partner harvests beavers. The plants are red willow and wintergreen. The sky is mostly stars here because the days are at their shortest and the nights are long.

Altogether, the piece represents natural cycles and our connection, as well as our dependence as living beings on those natural cycles.

In my original design I had planned to name the four seasons in the language: ziigwan (spring), niibin (summer), dagwaagin (autumn), and biboon (winter). I decided not to include the words, as I do in most of my work, because I think of woodland art as a written language rather than just an art style.

Anishinaabe people have always used images to portray stories, thoughts, and teachings, traditionally as pictographs and birch bark scrolls. Now we mostly do colourful paintings and beadwork in the woodland style. I am happy to share this with you.

Miigwech.

−Mishiikenh Kwe

Clan medallions were painted by artist Debbie Jackson from Wasauksing First Nation. The original paintings are on display at Killbear Provincial Park.

Odoodemaawin: The Clan System

Being a good relative is a hallmark of Nishnaabe life and society. So too is living in balance, contributing to community well-being, and honouring relationships with the natural world. Odoodemaawin, the clan system, is one means by which Nishnaabe people have maintained a positive sense of order while making sure the political, social, health, and spiritual needs of communities are fulfilled. All Nishnaabeg are born or adopted into a clan family that is representative of a particular animal, bird, or water being.

The clan system was bestowed upon the Nishnaabeg as a spiritual means of support during a time of great hardship. The oldest stories recount the presence of seven original clans who first stood up to mentor and guide the people. In time, many other clans came forward to help ensure the well-being and growth of the nation. Each clan is distinct, with its own characteristics and responsibilities. Clan membership is a source of pride, identity, and connection. In formal Nishnaabe-style introductions, one’s clan is shared alongside one’s spirit name as an indication of its relative importance.

Among the Nishnaabeg, clan membership is inherited from one’s father. There are other First Nations people, such as the Iroquois, who inherit their clans through one’s mother. Even when not related by blood, clan members regarded each other as family. To help ensure the strength of the nation’s bloodline and strengthen ties between different clan families, one could not marry a member of one’s own clan. Individuals seeking their clan are encouraged to research their family tree, speak to recognized elders, or consult community historians. If these prove unsuccessful, a trusted spiritual person may be consulted to help retrieve a lost clan or facilitate adoption into an existing clan.

There is a revival of the role of the clan system in communities today. This includes an exploration of its role in governance, as well as any varied traditional responsibilities, such as community protection, teaching, medicine work, or strategic planning. Each clan also has its own teachings, songs, and dances. The tradition of holding clan feasts and wearing a beaded or quilled pin or pendant in celebration of one’s clan identity are again increasingly commonplace.

Communities have a variety of clans represented in their membership. Some historic clans in the eastern Georgian Bay region include bear (mkwa), beaver (mik), caribou (adik), catfish (waasii), crane (jijaak), eagle (mgizi), hawk (gekek), loon (maang), marten (waabzhesh), moose (mooz), otter (ngig), raccoon (esiban), sturgeon (nme), turtle (mshiikenh), and wolf (ma’iingan). The clan system remains an important source of resilience, strength, and connection in Mnidoo-gamii today.

−Waabishki-makwa, Dr. Brian D. McInnes, Wasauksing First Nation, University of Wisconsin